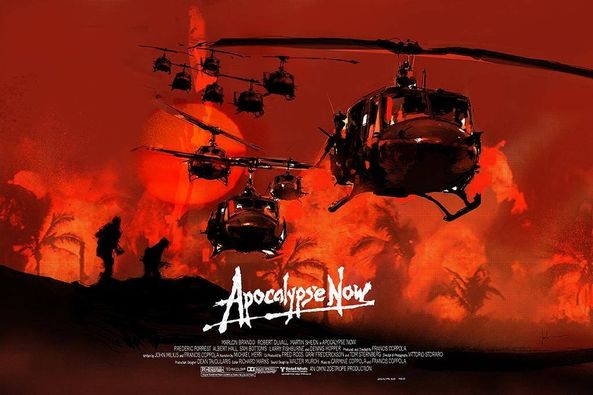

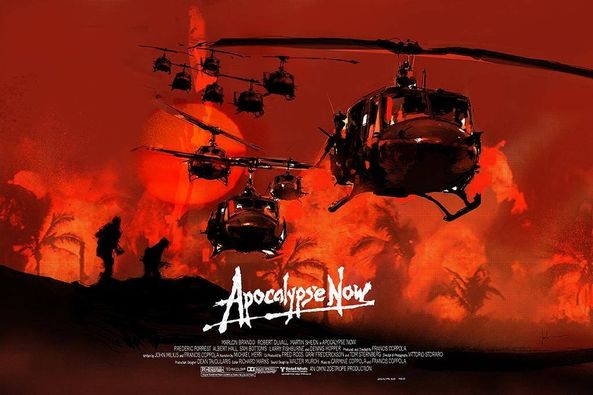

“Apocalypse Now,” directed by Francis Ford Coppola, is a haunting and surreal journey into the heart of darkness during the Vietnam War.

In the sweltering heat of the Vietnamese jungle, Captain Benjamin Willard trudged through the mud and dense foliage, his weary eyes scanning the horizon for any sign of civilization. War had become a fever dream, a descent into madness that blurred the line between sanity and chaos.

Willard had been given a mission, a mission that whispered in the shadows of his mind like a dark secret. He was to find Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, a decorated officer who had gone rogue, setting up his own kingdom deep within the Cambodian jungle. Kurtz had become a legend among the troops—a man who had embraced the horrors of war and turned them into his own brutal gospel.

As Willard navigated the treacherous river on a small patrol boat, the walls of jungle seemed to close in around him. The air was thick with the stench of death and decay, a constant reminder of the brutality that had consumed this land. His crew consisted of a ragtag group of soldiers: Chief, the stoic Native American who commanded the boat; Mr. Clean, the laid-back surfer turned soldier; Chef, the nervous and jittery cook; and Lance, the young and impressionable surfer who had joined the journey on a whim.

Their journey took them through a series of surreal and nightmarish encounters—a USO show interrupted by mortar fire, a French plantation owner clinging desperately to a colonial past, and a chaotic attack on a Vietnamese village where innocence was lost in a hail of bullets.

As they moved deeper into the heart of darkness, Willard became increasingly obsessed with Kurtz. He listened to recordings of Kurtz’s voice, his words haunting and hypnotic, like a man possessed by demons. Each step closer to Kurtz revealed more about the true cost of war—not just the lives lost, but the souls corrupted and the humanity stripped away.

Finally, they reached Kurtz’s compound—a surreal fortress shrouded in mist and guarded by devoted followers who worshipped him like a god. The atmosphere was heavy with an eerie calm, broken only by the occasional sound of chanting or the sight of bodies strung up as warnings.

Inside, Willard confronted Kurtz—a man who seemed both broken and transcendent, a figure who had embraced the darkness within and found a perverse kind of peace. Kurtz spoke of horrors committed in the name of duty, of the necessity of brutality to achieve order in chaos. His words were a chilling indictment of the madness of war, a mirror held up to Willard’s own fractured psyche.

In the end, Willard made a choice—a choice that echoed the futility of the war itself. He fulfilled his mission, but at what cost? As he floated down the river, leaving behind the madness and the horror, he knew that he could never truly leave it all behind. The war had changed him irreparably, leaving scars that would never heal.

“Apocalypse Now” was more than a film—it was a journey into the heart of darkness, a haunting exploration of the human soul in the grip of war’s insanity. Directed by Francis Ford Coppola, it remains a powerful and unforgettable testament to the horrors of conflict and the fragility of humanity.